ALIA Schools Online Forum: online learning – Day 1 Welcome to the first day of the ALIA Schools Online Forum: online learning. Everyone is welcome to participate and there are no registration requi…

Final Reflection…what do you think?

Quote

Image retrieved from http://thefabweb.com/43884/30-best-quotes-in-pictures-of-the-week-may-19th-to-may-26th-2012/

Learning is always a time for questioning, interpreting and reflecting. This Information-Learning Nexus Unit has enabled me to engage with a wide variety of inquiry processes and information literacy models, these have reignited my curiosity for learning but this time the learning is in context offering all learners the opportunity for deep, interconnected, passionate thinking and problem solving, preparing “students for work, citizenship, and life in a free society” (Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari, 2007, p. 14). As I reflect back to my initial inquiry questions I can appreciate my personal learning journey even more passionately. With renewed energy I feel empowered to be a part of the changing teaching and learning paradigm that the 21st century offers us as educators. “The 21st century calls for new skills, knowledge and ways of learning to prepare students with abilities and competencies to address the challenges of an uncertain, changing world” (Kuhlthau, 2010, p.2). With change we are taking a risk but change with passion brings a chance to make a difference in the classroom, in thinking, in learning, in society and in the world. Who wouldn’t want to be a part of this?

What is inquiry learning?

This investigation now ends with research from Carol Kuhlthau who initially started me on my inquiry journey, where she explains this process as going “beyond merely fact-finding to personal understanding” (2010, p. 4). The inquiry method of teaching and learning is “built on the basic desire of the human mind to understand the world that we live in” (Treadwell, 2008, p. 76) and now together with the real and authentic experiences explored through this unit I am excited by this opportunity to show others how to get more out of learning. This journey has enabled me to deeply explore Inquiry Based Learning (IBL) in a scholarly manner.

“Inquiry learning requires a rich information and communication environment that can provide a baseline for connectivity and knowledge …to build new knowledge and new concepts” (Treadwell, 2008, p. 76) “Inquiry sparks learning in students and …calls on the collaborative expertise of librarians and teachers” (Kuhlthau, 2010, p. 3) “Inquiry learning is a constructivist pedagogy that takes student-posed questions as the starting point for learning” (Lupton,2012, p. 12) “To inquire means “to ask questions” …so where did the question mark come from? No one is quiet sure, but it is powerful. This mark signals a question, which may begin a search and eventually find an answer…or bring to mind another question or two.” (King, Erickson & Sebranek, 2011, p. 235)

Image retrieved from http://www.schrockguide.net/bloomin-apps.html

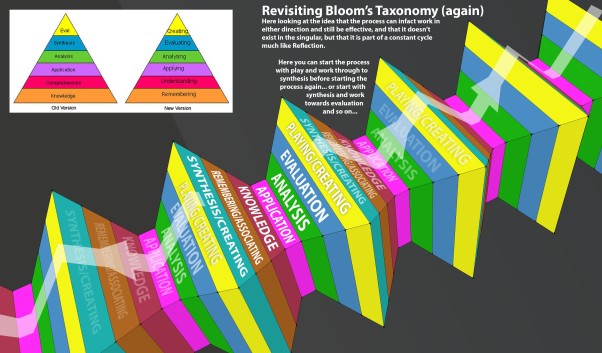

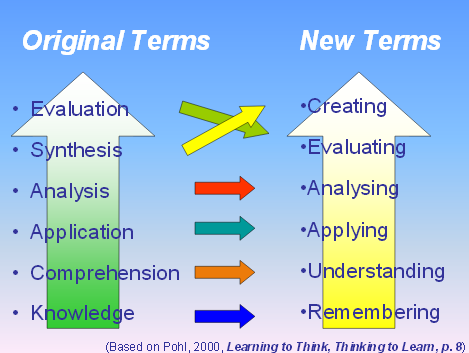

Upon reflection when I contrast this with Bloom’s Taxonomy I no longer just know about the inquiry process but have moved beyond application and analysis to being able to create my own IBL activities in the classroom grounded upon the evaluations made in this blog and my own personal learning. The questions asked initially have helped inform me during the Information Search Process (ISP) where through my own inquiry into IBL connections to these stages were experienced. IBL offers the 21st century teacher and learner the ability to work collaboratively, construct their own knowledge based upon prior learning ensuring motivation is high and that most importantly “learning centered” (Kuhlthau, 2010, p.5). With the ability to undertake five different kinds of learning (Kuhlthau, 2010) simultaneously during IBL this has to be the most effective approach to learning in the 21st century. What do you think?

What does expert inquiry learning look like?

I initially questioned what best practice would look like. Kuhlthau (2010) describes Guided Inquiry (GI) to be an inquiry methodology used to gain knowledge and deeper lifelong understandings. My school had used various models such as Hunter’s WE SOLVE It! Cycle of Inquiry, the Big 6 and the N.S.W. Department of Education I.S.P. However, we were not implementing any of these well.The further this investigation took me the more reassured I was that it sounded like chaos to those who hadn’t heard about this before.

As the GI team started to collaborate and refine each others roles there was a renewed sense of who was responsible for the different aspects of learning. We had created the “third space” (Kuhlthau, 2007) and I now look forward to working together when assessing curriculum, information literacy, meta-cognition, literacy and cooperation skills where we can “take learning to a higher level – to raise the bar as well as facilitate the sharing of experiences, successes, and obstacles along the way” (Kuhlthau & Maniotes, 2010, p. 21).

Expert inquiry learning takes into consideration student background knowledge and enables the teacher’s mandated curriculum to be incorporated solving the crowded curriculum conundrum. Having seen the benefits of moving from the Generic window (Lupton & Bruce, 2010) I am excited about the future and aim to help learners become critical thinkers who challenge others and the world around them. The need for information literacy to be seen as transformative will be achieved when “learners are empowered to challenge and question social norms, governments and employers” (Lupton & Bruce, 2010, p. 22) and these are skills that all 21st century learners will need to learn about and practise.

How do we recognise the critical moment when we are to intervene?

Initially I asked how much time would be used to ask the deep and rich questions that stretch research – all at just the right time. This has been a challenging skill as questions “are the most powerful tools we have for making decisions and solving problems – for inventing, changing and improving our lives as well as the lives of others” (McKenzie, 2005, p.15) and to make this even more thought-provoking “questions should always be purpose driven” (Godinho & Wilson, 2004, p. 4). The generation of deep student driven questions enables the teacher to assess meta-cognition and the real understandings that have been achieved.

Some initial questions I can now answer were all pedagogical and will depend upon the learners and the support offered by the team leading the inquiry.

- What will this time look like?This will be different for everyone, some students will be able to ask big questions and others will need guiding and scaffolding in order to ask higher level questions. Teachers too will need to be aware of thinking about the kinds of questions they are using and develop questions that “involve distilling and synthesising” (Treadwell, 2008, p. 90).

- How will I know when to do this stretch? As educators we are called to be aware of learning needs and intervene at just the right time. The inquiry process opens the gate to who can support and stretch thinking and enables other experts to offer their opinions and think about their thinking too.

- How can we guide and not give away the information?This all begins with effective questions, as “without effective questions the most educators can expect is regurgitated learning” (Treadwell, 2008, p. 101) and together with a strong inquiry process the opportunity for deep and transformative learning is achievable.

- Is there a best search model to follow? The Information Search Process (ISP) that is described by Kuhlthau (2010) offers deep learning and thinking. I have investigated many other models over this unit and will continue to learn about new ones as they are published. In fact Pearson Education have just published a new methodology called the Brainstorm, Define, How? (BDH) as alternative questioning tool that is useful in the Australian Curriculum. Learning and questioning are part of the ISP and this process leads to building an effective, creative,deep thinking, lifelong learner. It is my aim to be a lifelong learner.

After action research on this topic of inquiry, it is clear to me that Kuhlthau, who stated, “an inquiry approach is a most efficient way to learn” (2010, p. 6) is indeed correct! What do you think?

References:

Education Broadcasting Association. (2004). What is inquiry-based learning? Retrieved November 10, 2013, from http://www.thirteen.org/edonline/concept2class/inquiry/index.html

Godinho, S. & Wilson, J. (2004). How to succeed with questioning. Curriculum Corporation. Carlton South.

King, R. Erickson, C. & Sebranek, J. (2011). Inquire: A Guide to 21st Century Learning. Hawker Brownlow Education. Moorabbin.

Lupton, Mandy and Bruce, Christine. (2010). Chapter 1 : Windows on Information Literacy Worlds : Generic, Situated and Transformative Perspectives in Lloyd, Annemaree and Talja, Sanna, Practising information literacy : bringing theories of learning, practice and information literacy together, Wagga Wagga: Centre for Information Studies, pp.3-27.

Kuhlthau, Carol. (2010). Guided inquiry : school libraries in the 21st century School Libraries Worldwide, 16 (1), 1-12.

Kuhlthau, C. C., Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A. K. (2007). Chapter 2: The Theory and Research Basis for Guided Inquiry. In Kuhlthau, C. C. ; Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A. K. Guided inquiry : learning in the 21st century. Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited

Lupton, Mandy. (2012). Inquiry skills in the Australian Curriculum Access, 26 (2), 12-18.

McKenzie, Jamieson. (2005). Learning to question to wonder to learn, Washington: FNO Press,

Treadwell, M. (2008). The Conceptual Age and the Revolution Schoolv2.0. Australia: Hawker Brownlow Education. Moorabbin.

Recommendations – the future of information-learning

“The creative process involves getting input, making a recommendation, getting critical review, getting more input, improving the recommendation, getting more critical review… again and again and again.” Unknown

The action research conducted in this ILA has offered me the opportunity to really understand the relationship between information and learning. I now appreciate the interconnected nature of information literacy (IL) and inquiry based learning and acknowledge that the real area to develop is that of questioning. “By combining the underlying concepts of information literacy with major subject area curriculum standards, Guided Inquiry prepares students” (Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari, 2007, p. 91) to collaborate passionately in order to transform their learning. The introduction of an information search process has given this action research direction.

The ILA Team Approach

This ILA was led by a three-member instructional team. We enjoyed the “synergy for sharing ideas and creatively planning and solving problems” (Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari, 2007, p. 48) collaboratively. I had initially shared Dr Cornelia Brunner’s Inquiry Process Model where the questioning framework was felt to be naturally imbedded. The use of some templates that were offered on this website enabled the students to feel more confident in their initial musings on the topic. This team approach is something that I recommend and in this ILA demonstrated to the students that we were collaborating effectively and respectfully which is seen to be a vital component to 21st century teaching and learning.

The Use of Formative Assessment

After each session that has since become known as “Peer Mentoring” across the Year 3 and 4 teams, we were often discussing things that worked and didn’t work in order to refine the inquiry process as we went. We were consciously aware of using formative assessment by “finding out where learners are in their learning, finding out where they are going, and finding out how to get there” (William, 2011, p.45) and again the roles were being refined. I was aware of my role as “resource specialist, information literacy teacher and collaboration gatekeeper” (Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari, 2007, p. 57) and see the importance of being able to access information at just the right time as vital.

We were able to see, based on survey 1 results, that there was a specific need to improve web site evaluation. We spent some time deciding what to use (Kathy Schrock, CARS, Brunner ideas) and an explicit teaching moment was led by me. This was a success but workshops in smaller groups would have been more successful, better meeting the specific needs of the individual inquiry topics. This also meant that too much time was spent on finding resources and interpreting information. Another weakness linked to time management was that after getting 3-4 weeks into the inquiry process I anticipated that to do survey 2 and then only one week later conduct survey 3 would not demonstrate an incredible difference and also, more importantly, lose valuable research time. Therefore after consultation with the teaching team decided to spend more time on the I.S.P. as it was observed that the students needed more teacher direction and support in this area. The benefit of utilising the time in this manner enabled students to complete their inquiry before the school holidays benefiting me and the teachers who have been able to begin a new inquiry in collaboration with me in Term 4.

Pre-assessments were not conducted in this ILA and could have prevented declining interest across the inquiry process. The majority of students indicated an elevated interest as seen in the ILA results which can be attributed to the freedom of material choice and the movement within the Kuhlthau’s ISP model from the exploration phase to the formulation phase where more clarity is felt and thoughts were more focused.

Successes…what worked

Image retrieved from http://www.desicomments.com/desi/success/

There are obvious aspects that were seen to be successful in this inquiry and fortunately due to initial discussions the teaching team all shared a “constructivist view of learning, team approach to teaching” (Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari, 2007, p. 52) and were enthusiastic about this opportunity to learn more about the inquiry process. There was also a shared understanding of various information seeking processes leading to strong pedagogical discussions. The use of the SLIM Toolkit ensured formative assessment was enacted upon. We were about to teach vital critical literacy skills using the CARS model when we decided that the 5 W’s of Web Site Evaluation supported our student and the Brunner Inquiry process more closely. The introduction of various search strategies was also a highlight and students were excited to be using search engines other than Google. Note taking strategies were also improved in the ILA and this skill has proven to remain strong in recent observed sessions. The collaborative teaching team approach has changed the learning community, strengthened relationships and ensured the achievement of a more personalised learning focus. Students too, were highly motivated and felt supported by working in teams. Wilson discusses this and says “when given the opportunity to choose the focus of an inquiry, students are generally more motivated and ready to keep going when faced with challenges” (2013, p.7) and this was evident throughout the inquiry. The renewed understanding not only of the physical location and use of print resources (such as encyclopedias) but the use of the OPAC was another aspect where the learning environment was personalised.

Improvements…what didn’t work

In this ILA there was a lot of time spent finding resources and interpreting information. Time was considered to be precious as it was a 5 week period of time we were limited to. The overload of information needed time spent on management both of time and data. After reading about how to recognise time-wasting behaviour in Activate Inquiry by Jeni Wilson (2013, pp. 36-37) I was able to identify the procrastinators, hunters and gatherers, completion avoiders and frequent flyers amongst the class. The teaching team shared many inquiry process models and it would be interesting to visually and explicitly teach one model as we were getting ideas from two different models.(Brunner’s Inquiry Process and The N.S.W. Department of Education I.S.P.) Another aspect of improvement is that of using prior knowledge to more specifically inform teachers what the needs of individual groups are. The use of formative assessment was innate due to the school focus on this area however consideration of self and peer feedback could have been imbedded into the assessing stage (The N.S.W. Department of Education I.S.P.) of the inquiry. Assessment during inquiry learning needs to cover “concepts, understandings, behaviours, skills and dispositions” (Wilson, 2013, p. 74) and this is supported by ACARA who uses the term capabilities. Treadwell (2008, p. 64) discusses learning dispositions to include;

- being curious, imaginative and passionate

- to think laterally

- being meta-cognitive

- to be aware of the “big picture”

- being in/inter/dependent, critical thinkers

- willing to modify and adapt our world view

- able to provide reasons

- to act in a responsible, caring manner

- being capable and willing to be strategic

- to be persistent

The thinking skills that underpin these dispositions “need to be explicitly taught and reinforced so that they become habits … that are applied … thoughtfully” (Treadwell, 2008, p. 64) and with wisdom. These dispositions can be mapped against the “Habits of Mind” and Bloom’s Taxonomy and if incorporated would have a multiplying effect on learning. This all begins with effective questioning.

Image retrieved from http://billsteachingnotes.wikispaces.com/Habits+of+Mind

Image retrieved from http://apopheniainc.wordpress.com/2013/02/13/a-quick-look-at-a-new-view-of-blooms-taxonomy-wip/

Recommendations

Based upon research undertaken during the ILA there are three recommendations that would improve Guided Inquiry in the classroom. The following changes would improve and strengthen future inquiry processes; development of deeper questioning skills, an adoption of an Information Based Learning (IBL) approach and the integration of assessment strategies.

Adopting a questioning model is pivotal to learning how to learn and becoming a lifelong learner. “Questions and questioning may be the most powerful technologies of all” (McKenzie, 2005, p. 15) and coupled with new and transformational digital technologies we are in a unique time of educational change. The use of a simplistic KWL and Wonder Wall had been a great start but looking more deeply into A Questioning Toolkit (McKenzie, 2005, p. 29) in the image below you will see question types. It is strongly recommended that different questioning models be integrated into each year level. Therefore there would effectively be seven models that students would be able to refer to and bring to their learning in the senior years.

Image retrieved from http://fno.org/nov97/toolkit.html

Information Based Learning (IBL) coupled with a questioning model creates a strong inquiry model. This ILA has demonstrated clearly the benefits of an inquiry approach towards deep learning. The Microsoft Partners in Learning created a 21st Century Learning Design Rubrics and this describes six important skills that students need to develop to be;

- collaboration

- knowledge construction

- self-regulation

- real-world problem-solving and innovation

- the use of ICT for learning

- skilled communication

Assessment during the ILA was through teacher-student conferecnes, observations and anecdotal records. There is an opportunity to incorporate stronger records that demonstrate evidence of student learning and the use of graphic organisers, journals and concept maps would be beneficial in the future. Checklists could be given to specific team members to record the demonstration of skills, dispositions, behaviours or capabilities that need reviewing. It would be recommended that an assessment strategy be integrated into the IBL approach. Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari acknowledge that there are “five interwoven, integrated kinds of learning” (2012, p. 8);

- Curriculum content

- Information literacy

- Learning how to learn

- Literacy competency

- Social skills

Through an IBL approach lifelong learning is developed and students are exposed to an engaging and challenging learning environment. The IBL approach has a focus upon social construction (Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari, 2007, p. 27) is collaborative by nature, constructivist and learner centered – what other way is there to go forward into the next teaching and learning paradigm?

References

Kuhlthau, C.C., Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A.K. (2012). Chapter 1: Guided Inquiry Design: The Process, the Learning, and the Team. In Kuhlthau, C. C. ; Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A.K. Guided inquiry design : a framework for inquiry in your school. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

Kuhlthau, C. C., Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A. K. (2007). Chapter 2: The Theory and Research Basis for Guided Inquiry. In Kuhlthau, C. C. ; Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A. K. Guided inquiry : learning in the 21st century. Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited

McKenzie, Jamieson. (2005). Learning to question to wonder to learn, Washington: FNO Press,

Treadwell, M. (2008). The Conceptual Age and the Revolution School v2.0. Hawker Brownlow Education. Heatherton.

William, D. (2011). Embedded formative assessment. Solution Tree Press, Bloomington

Wilson, J. (2013). Activate Inquiry: The what ifs and the why nots. Education Services Australia, Carlton South.

Action – Stations are the go!

Action is the foundational key to all success.Pablo Picasso

Image retrieved from: http://debseed.wordpress.com/2012/02/26/individual-differences-the-affordance-of-multimedia-in-engaging-and-supporting-low-knowledge-learners/

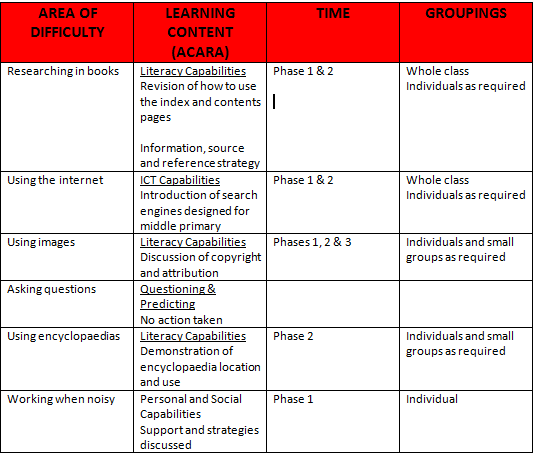

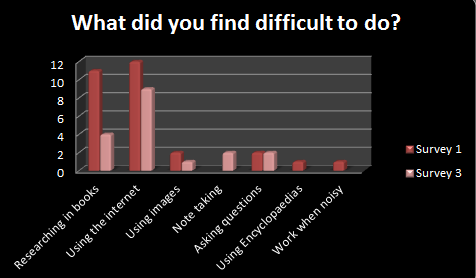

Research undertaken during Phase 1 of the ILA enabled me to gather important data that was used to guide and scaffold further learning. This data was shared with the learning team that consisted of the two classroom teachers and myself. Assessment “should form the backbone of your planning and inform your teaching and learning decisions” (Wilson, 2013, p. 72) so using the results from Question 5 in Questionnaire 1 the learning team was able to respond to the common needs of the cohort. This initial survey guided what we now knew about students’ thinking, research skills and research behaviours. Commonly identified areas of difficulty after the initial survey were;

- Researching in books

- Using the internet

- Using images

- Asking questions

- Using encyclopaedias

- Working when noisy

During this inquiry process there were two main areas of responsibility; resources and internet usage. This is supported by Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari who view the school librarian as an “indispensable member of the instructional team” (2007, p.57). Inquiry learning is “the most challenging part of the role, requiring many skills, including intuition, insight, collaboration, flexibility and at times, enormous amounts of persistance” (Green, 2012, p.19). The information search process undertaken in this inquiry was not specific and the ILA was a busy time where small groups of students were working independently making this a perfect time to intervene and support the learning.

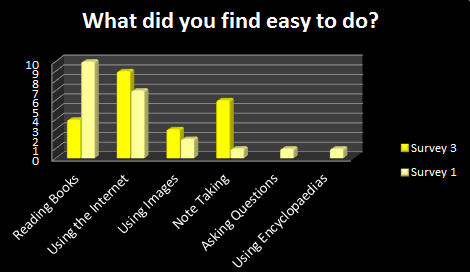

The Information Process (ISP) used was loosely based upon New South Wales ISP. Support was required during the locating, selecting and organising stages of the inquiry. As internet usage was the greatest area of difficulty I set about planning a whole class introduction to search engines during Phase 1 of the ILA. Demonstrations of Duck Duck Go, Quinturakids and Zuula were then presented and students had time to research in small groups or individually using computer nodes and iPads in the Discovery Centre. This lesson was followed by another informative session for the whole class based upon web site evaluation. We used Kathy Scrock’s The 5 W’s of Web Site Evaluation and made the Who, What, Why, When, Where and Why into a puzzle that groups put back together. The ICT capabilities of students has improved and can be seen graphically in the results. Using the internet was the easiest thing to do when students answered question 5 in Questionnaire 3 the second survey undertaken in the ILA.

The second area of difficulty identified from Questionnaire 1 was that of researching in books. Todd, Kuhlthau and Heinström recognise that during this time “instructional interventions typically focus on establishing information quality and relevance” (2005, p. 17) and guided inquiry is more than just finding information. During Phase 1 and 2 I was able to directly teach students how to use the contents and index pages in non fiction materials. The students were introduced to a information, source, page (I.S.P.) graphic organiser that we used to explicitly teach referencing. There was always time made for individuals who needed support with the location of resources in the Discovery Centre. Independent student use of the OPAC was good but some reminders of the geographical book locations was needed due to the age group of the students and the fact that these students were accessing non fiction resources from the main collection not just the Junior Room, some for the first time.

The actions taken enabled students to become independent learners who were able to collaborate, make meaningful connections and respond with authenticity to transform their learning. I attended Jeni Wilson’s recent Melbourne based PD on Activate Inquiry where the idea of small workshops that students can elect to do was introduced to me. Wilson strongly links meta-cognition to self-management and inquiry. Intervention is not just teacher directed but needs to be student centred Importantly “intervention strategies that foster reflection for deep understanding and basic inquiry abilities” (Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari, 2007, p.146) are valuable and this process of professional reflection has helped me to better understand inquiry as a “messy process” (Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari, 2012, p.2) and as Edna Sackson writes, inquiry can sound like chaos to those who don’t know about it!

References

Green, G. (2012). Inquiry and learning : what can IB show us about inquiry? [online]. Access; v.26 n.2 p.19-21; June 2012. Availability: <http://search.informit.com.au.ezp01.library.qut.edu.au/fullText;dn=193381;res=AEIPT>

Image retrieved from http://debseed.wordpress.com/2012/02/26/individual-differences-the-affordance-of-multimedia-in-engaging-and-supporting-low-knowledge-learners/

Kuhlthau, C.C., Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A.K. (2012). Chapter 1: Guided Inquiry Design: The Process, the Learning, and the Team. In Kuhlthau, C. C. ; Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A.K. Guided inquiry design : a framework for inquiry in your school. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

Kuhlthau, C. C., Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A. K. (2007). Chapter 2: The Theory and Research Basis for Guided Inquiry. In Kuhlthau, C. C. ; Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A. K. Guided inquiry : learning in the 21st century. Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited

Todd, R., Kuhlthau, C.C. & Heinstrom, J.E. (2005). School Library Impact Measure. A Toolkit and Handbook for Tracking and Assessing Student Learning Outcomes of Guided Inquiry Through The School Library. Center for International Scholarship in School Libraries, Rutgers University. Retrieved August 6th, 2013 from http://cissl.rutgers.edu/joomla-license/impact-studies?start=6

Wilson, J. (2013). Activate Inquiry: The what ifs and the why nots. Education Services Australia, Carlton South.

Analysis – theories enacted

Image retrieved from http://justhappyquotes.com/tag/funny-quotes/

This research based learning experience in the Information Learning Nexus unit has opened my eyes to the theory and practice of inquiry learning. Working as a team in the ILA allows us as educators to help our students enter the new learning paradigm as described by Ken Robinson. Gilbert recognises that one defining feature of this change is that of the new and different ways of thinking. This change is can be seen by moving from a point of knowing to a focus on understanding and application of this new learning. Even though inquiry activity contrasts with traditional education methods, information literacy should be a part of inquiry learning because evaluating the quality of information is important in inquiry-based learning and students use”real” questions in their inquiry-based learning. This view is supported by Treadwell who sees the development of inquiry learning as a “core capability in developing lifelong learning capability within the move to the emerging education paradigm” (2008, p.75).

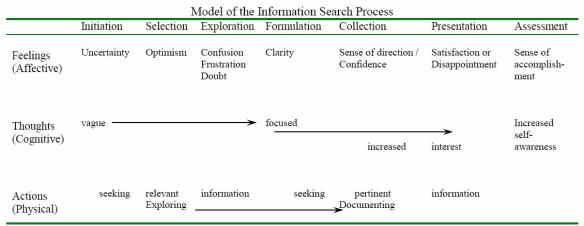

Information Literacy

Information Literacy (IL) is an important process where locating, searching, selecting and organising information is essential. Throughout this ILA reference was made continually to the Model of Information Search Process (Kuhlthau, Maniotes and Caspari, 2007, p.19.) and the stages that we were entering. Although the INITIATION stage was teacher guided there was freedom within the student body to make individual topic SELECTION. The EXPLORATION stage was a strength in this action research. However, recommendations will be made for improvements in the FORMULATION stage. Moving from the COLLECTION to the PRESENTATION stages were also easily achieved. ASSESSMENT was teacher driven and could include self and peer reflection in the future.

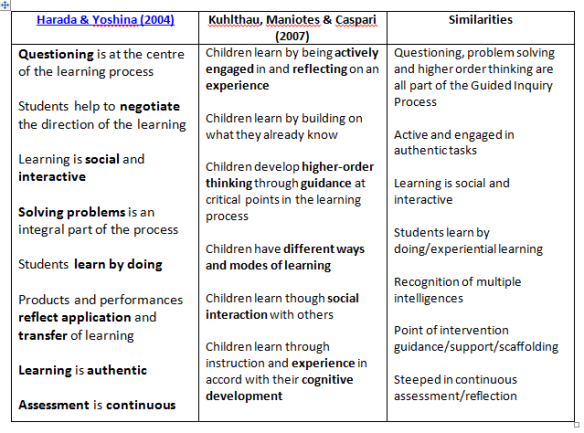

Guided Inquiry

The Guided Inquiry process that I utilised was that of the collaborative, team approach described by Kuhlthau, Maniotes and Caspari (2012). After discussing the ILA with class teachers it became evident that we all supported the features of an inquiry learning classroom as outlined by Harada & Yoshina (2004) where features included questioning, negotiating, social interaction, constructivist approaches and problem based learning through out the inquiry process. The table below demonstrates similarities between Harada & Yoshina (2004) and Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari (2007) helping to ensure all involved in this process shared 21st century learning skills.

ACARA

The consideration of the Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) Creative and Critical Thinking F-10 Continuum and the Science Curriculum was utilised in order to connect curriculum with the students world. There is reference to a clear inquiry process in the ACARA documentation and strong similarities to the AASL standards for the 21st century leaner were previously documented. The strong links to meta cognition are documented as a series of four steps;

- Inquiring – identifying, exploring and organising information and ideas.

- Generate ideas, possibilities and actions

- Reflecting on thinking and processes

- Analysing, synthesising and evaluating reasoonging and procedures

More and more often the ACARA content was covered by the class teachers and I was increasingly responsible for the critical and creative thinking. The table below illustrates comparisons between Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process, The Information Process (ISP NSW DET Model) and ACARA Creative and Critical Thinking F-10 Continuum.

The idea of utilising the “third space” as described by Kuhlthau, Maniotes and Caspari (2007) students were taking part in a learning centered world where the content became secondary due to the fact that each group was learning about something they were passionate about. The inquiry skills had a renewed focus. Overall there was a general increase in all areas between questions and this can be attributed to the ISP where students move to the Selection and Explanation stages of Kuhlthau’s ISP Model. The sheer increase in response quantity requiring extra pages and an explanation of the acronym P.T.O (please turn over) demonstrates an increase of higher order thinking. The mandated Science Understandings were easily achieved in this ILA and there was a targeted times where Science Inquiry Skills were taking the main stage.

Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy

During the action research conducted during the ILA consideration of Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy was used. The simplistic remembering layer was not required. Rather students were needing to understand and explain their concepts and apply this new knowledge in order to make analytical connections between the scientific concepts of living and non living and the properties of associated materials and their influences. This culminated in the creation of a variety of works such as speeches, models, experiments (some that failed three times) persuasive brochures adn dramatic plays. All groups generated new ideas or products.

During the action research conducted during the ILA consideration of Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy was used. The simplistic remembering layer was not required. Rather students were needing to understand and explain their concepts and apply this new knowledge in order to make analytical connections between the scientific concepts of living and non living and the properties of associated materials and their influences. This culminated in the creation of a variety of works such as speeches, models, experiments (some that failed three times) persuasive brochures adn dramatic plays. All groups generated new ideas or products.

GeST Windows

Information Literacy has been described by Lupton and Bruce (2010) as a Generic, Situated and Transformative (GeST) paradigm. The three windows are seen to have an inclusive relationship where literacy is seen as;

- a set of generic skills (behavioural)

- situated in social practices (sociocultural)

- transformative, for oneself and for society (critical)

These perspectives can be seen to be nested inside each other and in this ILA a variety of windows were achieved by different groups. The students who stayed in the generic window were generally working by themselves and saw their inquiry as finding answers to questions and presented their learning via powerpoint presentations. The skills of finding, locating, selecting and organising information were challenging and further guidance to “examine currency, bias, authority, provenance” (Lupton and Bruce, 2010, p. 12) would have benefited this group. Alternatively revision of how to evaluate internet sources would have been timely. The majority of groups were operating in the situated window using many information search strategies and solving personally selected inquiries in a social setting. This too was problematic as some groups had trouble staying on task and kept going back to the defining stage.

It is my personal aim to strive towards the transformative window where the “skills and processes of the Generic window and the authentic social practices and personal meaning” (Lupton and Bruce, 2010, p.13) are coupled together with deeper reflective critical thinking taking into consideration the social influences. One group did make transformational change as their learning led to transformational thinking where the depth of their knowledge specifically on koalas inspired them to publish a brochure to help others understand the issues and seek change. This group inspired the class during the presentation stage to become active environmentalists. The success of this group was seen by the deep convictions held and the opportunity to make a difference in the world.

Conclusion

Best practice can be seen to based on social construction, where learning occurs through interaction. The teachers were learning about guided inquiry and the students were engaged and motivated throughout this ILA. The Six Principles of Guided Inquiry all share these aspects and when coupled with higher order thinking skills such as Habits of Mind make for transformational learning opportunities. “Guided Inquiry is based on the premise that deep, lasting learning is a process of construction that requires students’ engagement and reflection” (Kuhlthau, Maniotes and Caspari, 2007, p. 25). Together with ACARA standards and competencies, questioning models and information search processes the inquiry process with will give learners the essential tools required to emerge from our schools with the capacity to be independent lifelong learners, empowered to question and solve problems and issues creatively.

References

Harada, Violet and Yoshina, Joan. (2004). Chapter 1 : Identifying the inquiry-based school in Harada, Violet and Yoshina, Joan, Inquiry learning through librarian-teacher partnerships, Worthington, Ohio: Linworth Publishing

Kuhlthau, Carol C. ; Maniotes, Leslie K. & Caspari, Ann K. (2007) Guided inquiry : learning in the 21st century, Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited.

Kuhlthau, C.C., Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A.K. (2012). Chapter 1: Guided Inquiry Design: The Process, the Learning, and the Team. In Kuhlthau, C. C. ; Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A.K. Guided inquiry design : a framework for inquiry in your school. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

Treadwell, M. (2008). The Conceptual Age and the Revolution School v2.0. Hawker Brownlow Education. Heatherton.

Lupton, M., & Bruce, C. (2010). Chapter 1 : windows on information literacy worlds : generic, situated and transformative perspectives, in Lloyd, A., & Talja, S., Practicing information literacy: bringing theories of learning, practice, and information literacy together. Wagga Wagga: Centre for Information Studies, 3-37.

Results from the ILA

Retrieved from: http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/g/georgespa124616.html

The Results, the outcomes and my interpretation…

At the beginning of the Information Learning Activity (ILA) the students were asked to select a material to study and research the living and non living components of it. Using the School Library Impact Measure –SLIM Toolkit (Todd, Kuhlthau & Heinstrom, 2005) as measurement tool I was able to assess and track the guided inquiry process in great detail. I conducted two data collection surveys using the questionnaires were and making a change to the suggested time frame. The outcomes of this unit was tied into the ACARA Science Curriculum. For ease of interpretation results for questions 1, 2 and 3 in SURVEY 1 will be green and all SURVEY 2 results will be coloured in red.

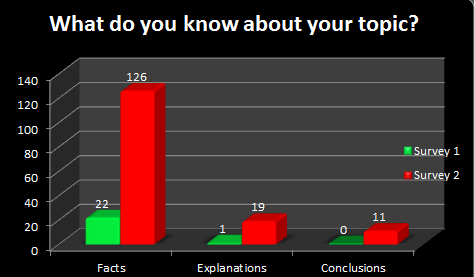

Question 1 – What do you know about your topic?

In these surveys students were asked to think about what they were learning about in order to focus their thoughts and to then write down what they knew about the topic. The student responses were analysed individually and responses to question 1 from both surveys was categorised into fact, explanation and conclusion statements as can be seen below in table 1.

This figure clearly demonstrates an increase in all three areas. However, one difficulty when scoring facts in question 1 was that some of the students were defining the general topic of living and non living things, rather than writing verb statements to describe “what a concept is or how it is performed” (Todd, Kuhlthau & Heinstrom, 2005, p. 7). Whilst recording results for Questionnaire 1 I noticed there was only one explanation and no conclusions made. I was worried that I had not explained the questionnaire correctly or that the students didn’t understand me. Some students wrote “we don’t know” even after the initial topic launch that was conducted voiding their responses. In the image below you will see the response from Student 6 who I decided to track more closely.

For the purposes of this data analysis, Students 1 to 6 were tracked individually. The various educational, social and emotional needs of these students varies greatly and will be seen in the detailed analysis. Student 1 made one very deep explanation in Questionnaire 1 and as this student is involved in the gifted and talented program I wondered if this would make a difference to the overall outcomes of this survey. Looking at the individuals inspired me to consider the total change in learning. To look at total change in learning I added up all fact, explanation and conclusion statements from Survey 2 and subtracted the total from Survey 1. This gave me a score that was averaged into the two groups of students. Again student 1 ranked the highest across the cohort and is a confident and optimistic person. However, interestingly the scores did not match preconceived learning needs and styles of others.

Overall there is a general increase in all areas between questions but interestingly the greatest improvement was seen in an increased factual knowledge demonstrated in Table 3.

Question 2 – How interested are you in the topic?

The SLIM Toolkit questionnaire asks students to consider how interested they are in their topic and below in table 4 you can clearly see the increased student interest between survey 1 and 3.

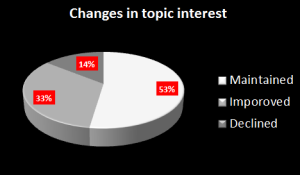

The pie graphs below enable you to see clearly the changes between each survey and then finally a comparison of grouped individual interest levels based upon changes. The grey pie graph despite demonstrating a 14% decline is representative of only 3 students.

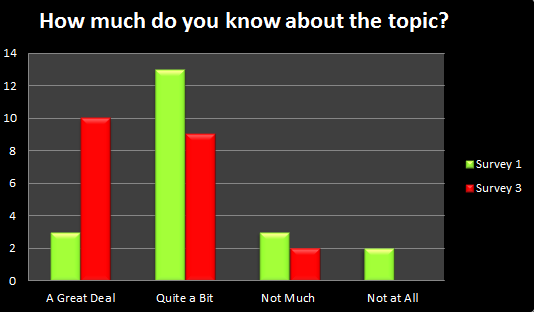

Question 3 – How much do you know about the topic?

This question displays student self awareness of topic knowledge. Table 8 depicts the quantitative data of student estimated knowledge on the topic. When surveyed at the end of the ILA some students wanted to make a fifth box entitled “everything”. This question was seen as formative assessment and helped me to prioritise who to track more closely and support. Overall despite the graph showing an increase in knowledge there were six students who scored the same in both surveys.

Question 4 – What did you find easiest to do?

Due to the age of these students results in this are were less than I expected possibly due to their age and ability to answer these questions cognitively. However the themes of information searching and usage of the internet were common across this research project. Students commonly responded to these questions in dot point and in similar ways as seen in this image. However, there were 6 questionnaires that were unable to be included due to absence during the survey 2 data collection phase. That being the case results could have been significantly higher.

The results in table 9 depict the collated student perceptions of the information search process and were broken into six common themes as seen below:

Question 5 – What did you find difficult to do?

The common themes of surrounding the information search process continued to be mentioned in the surveys. However, as can be seen in table 10 there were some significant changes that can be contributed to formative assessment strategies and discussion of this can be seen in the analysis. Again, there were four questionnaires that have been omitted in this survey due to absence and their common area of difficulty was in the area of internet usage and the strategy enlisted to elicit answers from Google. This table does not demonstrate the difficulty some groups had on staying on task. There were two particular groups whose topics changed in each session making information selection difficult due to the changing topic questions. The inclusion of work environment will be addressed in the analysis.

This pie graph does not reflect three students decline in interest levels but when looking at the raw data it was interesting to see the answers in question 5 and 6. Student 19 was not interested at all and found “nuthing (sic) hard to do” (SLIM Questionnaire 3) and interestingly stated it was because they “knew efreing (sic)” (SLIM Questionnaire 3). This student’s topic area was a common material that most Victorians study in depth and with parents who find and make holiday links to learning had selected something comfortable.

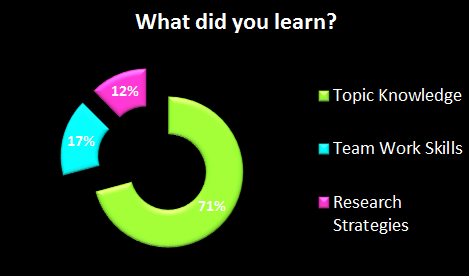

Question 6 – What did you learn in doing this research project? (Questionnaire 3 Survey 2)

Survey 2 used The SLIM Toolkit Questionnaire 3 and consisted of two additional questions to be answered. This second survey was conducted in a rush at terms end and enabled me to collect 25 responses. However, two students omitted this question. This question was designed to “generate a student-based summary of their learning” (Todd et.al., p.17) and data collected did not enable me to analyse information seeking strategies rather then main self perceived learning. Answers to this question were brief and tended to fall into the following three categories.

Table 12 below depicts a clear ring with percentages, again the strength in factual information based on the evidence above can be seen.

Question 7 – How do you feel about your research?

The ILA ended with a particularly high sense of achievement where the presentation of findings was a whole class celebration. There was a wide variety of materials and an even broader assortment of presentation structures ranging from models, power point presentations, role plays, television news reports, brochures and experiments. When adding the confident and happy responses together there is an overwhelmingly high percentage of 95% of students who are able to demonstrate their new knowledge with passion and assurance. There was one confused student who consistently selected broad questions, displayed and reported ongoing difficulty using the internet who could have benefited from tracking.

Outcomes and Interpretations

As seen in the gallery below students were able to “share the product they have created to show what they have learned with the other students in their inquiry community” (Kulthau, Maniotes & Caspari, 2012, p. 5). A clear ability to distinguish between living and nonliving things was achieved. Students were able to confidently report upon their selected materials describing a range of uses and their specific properties.This ILA was considered successful as we were able to achieve numerous ACARA content descriptors and the inquiry skills consisting of questioning, predicting and communication. Wilson accurately states that “assessment data should be used for planning and to ensure that students are actively involved in all aspects of the learning process” (2013, p. 72) and all teachers were part of the process making the learning journey a success.

- ILA Projects – own images

References:

Kuhlthau, C.C., Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A.K. (2012). Chapter 1: Guided Inquiry Design: The Process, the Learning, and the Team. In Kuhlthau, C. C. ; Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A.K. Guided inquiry design : a framework for inquiry in your school. Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

Kuhlthau, C. C., Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A. K. (2007). Chapter 2: The Theory and Research Basis for Guided Inquiry. In Kuhlthau, C. C. ; Maniotes, L. K. & Caspari, A. K. Guided inquiry : learning in the 21st century. Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited

Todd, R., Kuhlthau, C.C. & Heinstrom, J.E. (2005). School Library Impact Measure. A Toolkit and Handbook for Tracking and Assessing Student Learning Outcomes of Guided Inquiry Through The School Library. Center for International Scholarship in School Libraries, Rutgers University. Retrieved August 6th, 2013 from http://cissl.rutgers.edu/joomla-license/impact-studies?start=6

Wilson, J. (2013). Activate Inquiry: The what ifs and the why nots. Education Services Australia, Carlton South.

Methodology of the ILA

“Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn.”

― Benjamin Franklin

Retrieved from: http://appliedalliance.wordpress.com/2012/11/08/we-learn/

The Information Learning Activity (ILA) implemented during the last five weeks of Term 3 utilised the The School Library Impact Measure (SLIM) toolkit (Todd, Kuhlthau & Heinström, 2005) and “focused on the thinking skills and habits of mind that lead to greater understanding” (Harada & Yoshina, 2004, p. 1) where the characteristics of an inquiry based environment were able to be analysed using information learning theories and especially the Information Search Process (ISP).

The educational context of this ILA is considered formal where face to face interactions take place and I led 5 sessions as outlined previously. The inquiry focus was upon living and non-living materials with a group of 28 Year 3 and 4 students. The pupils completed two surveys throughout this time with 21 completing both surveys (12 girls and 9 boys). The surveys were conducted during my Discovery Learning sessions without the presence of their class teachers.

Data Gathering – the what, why, how and when

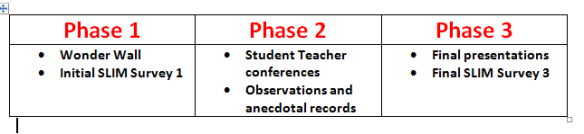

The school that this ILA is situated in is currently undertaking a whole school approach towards assessment. As ongoing assessment is one of the goals of guided inquiry the implementation of this project has been the perfect opportunity “for evidence-based practice” (Todd, 2010, p. 24) to be put into action. There were three phases of assessment and data collection as seen below. This was conducted across five weeks and the findings used to analyse and better understand meta-cognition and deep thinking in the inquiry process.

Phase 1 was conducted over a two week period where the the initial Questionnaire 1 was conducted with the whole class. During this time students were in the initial stages of their inquiry. Phase 2 incorporated the information search process, observations and student teacher conferences on a group of tracked students that took two weeks to complete. Phase 3 consisted of only one week due to timing of school holidays and affected how many surveys in total were able to be taken. Both Questionnaire 1 and 3 were used in order to seek data and further information on initial knowledge and post learning achievements.

All students had the freedom to present their findings in any way they liked and then orally presented to the class at the end of the term. This enabled the guided inquiry team to reflect upon the learning process and more importantly empowered the students to reflect upon their learning and make connections with the learning process and personal progress. Assessment was ongoing throughout the inquiry process as different skills were required at different times and as educators we had to determine the right time for point of intervention support.

The use of the SLIM Toolkit enabled me “to measure how students’ knowledge of their curriculum topics changed during the inquiry unit and track changes in interest and information seeking” (Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari, 2007, p.126). The data collected on the surveys was scored quantitatively in order to graph and analyse the findings. Using results from questions 1,2 and 3 comparisons were made between each Questionnaire. Other data was coded in a qualitative manner in order to find common themes around inquiry learning. The answers from questions 4 and 5 were open ended and after collation enabled me to target specific student needs. The results of this ILA have helped me see and appreciate the importance and value of inquiry learning.

References:

Harada, Violet and Yoshina, Joan. (2004). Chapter 1 : Identifying the inquiry-based school in Harada, Violet and Yoshina, Joan, Inquiry learning through librarian-teacher partnerships, Worthington, Ohio: Linworth Publishing

Kuhlthau, Carol C. ; Maniotes, Leslie K. & Caspari, Ann K, Guided inquiry : learning in the 21st century, Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited.

Todd, R., Kuhlthau, C. & Heinström, J. (2005). School Library Impact Measure S L I M – A toolkit and handbook for tracking and assessing student learning outcomes of guided inquiry through the school library. [PDF file] Retrieved from http://cissl.rutgers.edu/images/stories/docs/slimtoolkit.pdf

Todd, R. (2010). Curriculum Integration – Learning in a changing world. Camberwell. ACER Press

Standards for the 21st century Learner

Comparative Essay – AASL vs Australia

“It is the supreme art of the teacher to awaken joy in creative expression and knowledge.” – Albert Einstein

Retrieved from: http://www.txmrecruit.co.uk/blog/skilled-american-workers-to-fill-australias-labour-shortage/

There is a wide variety of educational standards and continua available in educational settings. The development of the Australian Curriculum gives insight into the creative and critical thinking skills used in our schools today and is a relevant and up to date document. The Critical and Creative Thinking Learning F-10 Continuum will be compared with the American Association of School Librarians (AASL) Standards for the 21st century learner. The purpose of this essay is to contrast the inquiry search process, dispositions and skills used and the responsibilities learners bring with them.

Firstly, the AASL standards document a very strong inquiry approach to learning. There are four stages that share similarities with many inquiry based models. Stage one begins with an inquiry based process where recognition to prior learning is made apparent. There is a strong questioning framework that continues into stage two. Stage two looks at analysis, synthesis, evaluation and organisation again representing the strength in the ISP. There is recognition of learning dispositions and skills where the learner is displaying initiative and engagement by posing questions. This demonstrated the importance of divergent and convergent thinking where information literacy is as important as “attitudes, emotions, values, ethics and motivation, are (also) critical in how they apply their understanding via the cognitive and practical skills” (Treadwell, 2008, p. 63). Logically the responsibilities all learners share are incorporated in stage three and four with respect to others and global perspectives also included. The ethical issues surrounding copyright and ICT responsibilities are importantly made a part of this four step process where students ultimately “pursue personal and aesthetic growth” (AASL, p. 4).

The second document to consider is the Australian Curriculum Creative and Critical Thinking F-10 Continuum. This too has four aspects but has been tabulated into levels that correlate into years (foundation to Year 10) across the Australian Curriculum. There is reference to a clear inquiry process similar to the AASL standards however; this is described in a simplified manner in comparison. Kuhlthau’s ISP stages can be likened to these easily, as can be seen in the table below. There is less emphasis placed upon learning dispositions in this document and sees this reflected in stage three where “thinking about thinking (metacognition)”(2010, p. 2) is referred to. Thinking skills need to be explicitly taught and reinforced so that they become habits as learning “dispositions have a multiplying effect on the ability of the learner to build knowledge into understanding and hence increase the capability for creativity and innovation” (Treadwell, 2008, p. 64). The last aspect of responsibilities is not clearly articulated in this document and relies upon the justification of the conclusions made.

|

Kuhlthau’s ISP Stages |

AASL |

ACARA |

|

Initiation |

Inquire think critically and gain knowledge |

Inquiring – identifying, exploring & organising information & ideas |

|

Selection |

||

|

Exploration |

Draw conclusions, make informed decision, apply knowledge to new situations & create new knowledge |

|

|

Formulation |

Generate ideas, possibilities & actions |

|

|

Collection |

Reflecting on thinking and processes |

|

|

Presentation |

Share knowledge & participate ethically & productively as members of our democratic society |

|

|

Assessment |

Pursue personal and aesthetic growth |

Analysing, synthesising & evaluating reasoning & procedures |

These two documents demonstrate a “research approach to learning” (Kuhlthau, 2010, p.2) and are both learner centered where there is commitment to the “construction of new knowledge in the stages of the inquiry process to gain personal understanding and transferable skills” (ibid., p. 5). There is clearly an importance placed upon information literacy in both documents and this is echoed strongly by AASL who included ethics and responsibilities. Both the AASL and ACARA documents looks at metacognition as can be seen by their use of ISPs as outlined in the table above. These standards and continua demonstrate that no matter what the curriculum content they are motivated to “learn subject area content and habits of mind through strategic interventions that enable them to make the learning their own” (Kuhlthau, 2010, p.8).

References:

Kuhlthau, C. (2010). Guided inquiry : school libraries in the 21st century. School Libraries Worldwide, 16(1), 1-12.

Standards for the 21st Century learner. (n.d.). Retrieved September 10, 2013, from http://w: ww.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/aasl/guidelinesandstandards/learningstandards/standards.cfm

Thinking Curriculum (n.d.). Retrieved September 10, 2013, from http://qutinquirylearning.edublogs.org/files/2013/07/CCT_F-10-2hhgly7.pdf

Treadwell, M. (2008). The Conceptual Age and the Revolution School 2.0. Heatherton: Hawker Brownlow Education.

Application of information-learning theories…it’s all about me!

“Live as if you were to die tomorrow. Learn as if you were to live forever.”

― Mahatma Gandhi

Retrieved from: http://theluckyvirgo.com/how-to-never-stop-learning/

On a bright sunny Sunday afternoon the light globe switched on in my mind…it was finally making sense! Information Learning Nexus was finally something to celebrate. I knew that I was learning about the learning and in my opinion any new learning is challenging. As Gandhi says, we are to learn and learn and then learn some more and after suffering a cold thought I too would die with all of this new learning! Inquiry learning to me was about asking questions and finding answers and this unit has enabled me to see just how powerful this framework can be. Kuhlthau states that “Inquiry is the foundation of the information age school” (2010, p. 2) and describes Guided Inquiry to be a collaborative team approach that enables students to “meet the challenges of an uncertain, changing world” (2010, p.3). This inquiry approach has enabled me to learn; information literacy, how I learn, the course content, improve literacy and even my social skills via Facebook.

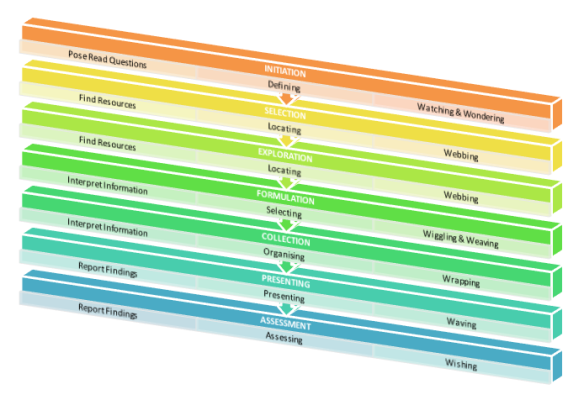

Kuhlthau’s Model of the Information Search Process (ISP) includes the following seven phases that are commonly experienced by the learner. Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari state that “learning begins with uncertainty and is driven by the desire to seek meaning” (2007, p. 17). Learning is complex and this ISP recognises feelings, thoughts and actions in which I will reflect upon. Other models have been investigated and similarities can be found between Brunner’s Inquiry Process, the Department of New South Wales ISP and The 8 Ws: Information Literacy as seen below.

Retrieved from http://www.virtualinquiry.com/inquiry/topic72model.pdf

The stages of these other models will be referred to at the end of Kuhlthau’s Model of the Information Search Process (ISP) reflections.

Stage 1 – Initiation

Retrieved from http://www.stevegutzler.com/emotional-hijacking/

At the very beginning of this unit my thoughts were fixated upon the spelling of inquiry versus enquiry. I know now that my sleepless nights and anxious mind was just the expected “uncertainty” that is a part of this stage in the ISP. Blogging was challenging and saw me pull out my notes from 2010 where I was first exposed to WordPress, but so much had changed – rather – so much was not really understood back then. The initial thoughts about this unit were broad and encompassed vocabulary such as the following acrynoms that were all new to me; IL, IL, ILA, ISP, KWL, KWHLAQ, GeST. I read as much as I could before the unit began but needed support in order to go forward. The weekly online collaborate sessions would give me just that! Looking back over my Week 1 to do list I can see that I was living in the dark, unfortunately there were nine things to follow up on in just that one session. I was “feeling depressed and bogged down and overwhelmed at the amount of work ahead” (Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari, 2007, p. 18).

Brunner’s Inquiry Process – Pose Real Questions

N.S.W. Department of Education I.S.P. – Defining

The 8Ws: Information Literacy – Watching and Wondering

Stage 2 – Selection

Feeling like a mushroom, I thought I was missing something. I was doing all of the readings and I was attending the online collaborate sessions but in my state of confusion I was disabled. The to do lists were growing but my ability to stay on top was zero. There were so many other things to select from and school events such as Science Week and Book Week took priority and prevented me from focusing on this topic or my ILA. This lasted for three weeks for me personally. Faced with a new topic, new concepts, new terminology, new lecturer, new work format (blogs) and new web 2 tools that were to be integrated the question of where to start was real and the uncertainty seemed to grow. After finally selecting a middle primary class to make links with, my focus changed and I felt I was getting on top of things and felt my optimism rising only to discover just how much work there was now to do.

Brunner’s Inquiry Process – Find Resources

N.S.W. Department of Education I.S.P. – Locating

The 8Ws: Information Literacy – Webbing

Stage 3 – Exploration

Retrieved from: http://www.flickr.com/groups/sporeprint/pool/

The exploration stage was difficult for me as my time was poor. I felt that there was so much out there to research and that narrowing it down was too hard. Often my search strings gave millions of hits and then using that same search string in another data base I would get nothing. Confused by what would and would not work soon became a frustration. This is demonstrated in my initial use of the A+ Education data base where the search string used in Google Scholar found zero results. I was “working through my own ideas and constructing new knowledge ” (ibid., 2007, p.18) and it seemed that I was now in the middle of the mushroom wondering which line of inquiry to select.

Brunner’s Inquiry Process – Find Resources

N.S.W. Department of Education I.S.P. – Locating

The 8Ws: Information Literacy – Webbing

Stage 4 – Formulation

This stage occurred while writing the Annotated Bibliography for this blog. I was so focused on my readings and summarising the main ideas and arguments that the light was not able to shine. After evaluating so many articles for their objectivity, reliability and bias I found myself using Kathy Schrock’s Five W’s of Web Site Evaluation and the CARS model when evaluating information. Thinking this is exactly what my middle school students need for my ILA I too felt I had a renewed sense of direction. When I had finished synthesising my ideas the light came on, there was renewed clarity. I was researching information on Guided Inquiry using the Guided Inquiry process. How clever!

Brunner’s Inquiry Process -Interpret Information

N.S.W. Department of Education I.S.P. – Selecting

The 8Ws: Information Literacy – Wiggling and Weaving

Stage 5 – Collection

Retrieved from: http://www.mmo-champion.com/threads/1115378-Pandaria-is-located-west-of-Kalimdor-Seems-like-it!?p=16422972

Feeling some what relieved that the Annotated Bibliography was complete I was ready to collate my findings and write the essay. Again the complex nature of learning with the world at our fingertips was evident. I was able to break my information into three areas in order to explain the information search process that I undertook. I was suddenly writing about questioning frameworks, the search process and the ability to reflect upon the learning in a collaborative and supported environment. There was renewed confidence in myself, I knew the topic. This transpired into allocating precious time to dedicate on this blog. This increased my sense of ownership and the blog began to grow both in content and readership (albeit family and friends) I felt I was “developing expertise”(ibid., 2007, p.20) and wanted to share this in my ILA at school.

Brunner’s Inquiry Process -Interpret Information

N.S.W. Department of Education I.S.P. -Organising

The 8Ws: Information Literacy – Wrapping

Stage 6 – Presentation

Retrieved from: http://www.risticrealestate.com.au/author/admin/page/

This is where I find myself right now – in the Presentation Stage. I am at the end of the Guided Inquiry ISP and am now ready to share my ideas with others. The feedback from my peers has been meaningful and seeing the blogs of others grow has been both elating and deflating. As I work full time and study part time there is a part of me that is disappointed in what I have not achieved after seeing some excellent online work. This is again articulated by Kuhlthau (2007) when she describes the aspect of reflection and self assessment. My peer reviews coupled with my own desire to improve saw me edit some posts in order to better present my inquiry findings. This leads me to the success or failure image and takes me to the last stage of the Information Search Process.

Brunner’s Inquiry Process -Report Findings

N.S.W. Department of Education I.S.P. -Presenting

The 8Ws: Information Literacy – Waving

Stage 7 – Assessment

This learning process is complex and very personal and all educators know the importance of assessment. I feel that what I now know about Guided Inquiry will benefit me in my teaching. As a inquiry learning facilitator I will be able to help others become life long independent learners. There is a “sense of accomplishment” (ibid., 2007, p.19) in seeing my work online, published to the world but with this comes an increased critical awareness where credibility, accuracy, reasonableness and support can be questioned. This Inquiry learning process has enabled far greater engagement in an authentic real world context. Success or failure is not important rather that I have been engaged in higher-order thinking processes and have been empowered to translate this into my ILA where my students and I will be transformed.

Brunner’s Inquiry Process -Report Findings

N.S.W. Department of Education I.S.P. -Assessing

The 8Ws: Information Literacy – Wishing

This table demonstrates the similar Information Search Process stages based on Kuhlthau’s Model of the Information Search Process (ISP) and have been compared with Brunner’s Inquiry Process, the Department of New South Wales ISP and The 8 Ws: Information Literacy process. There are many similarities across the processes. They are all cyclic in nature, strong in questioning and all have an aspect of assessment or reporting included. The Brunner Inquiry Process has classroom display appeal and would make an excellent visual reminder in any classroom. It seems to suit primary levels as it has a simple four level approach with simple questioning embedded into each stage of the inquiry process but lacks consideration of feelings, thoughts and actions that Kuhlthau’s model includes. The Department of New South Wales ISP also gives clear steps in the process and includes questions to support this inquiry. Consideration of the information skills used makes this model a preferred model for my middle primary students. This model focuses on quality teaching and would support formative assessment which complements cyclic learning processes. As much as I like the alliteration of the 8 Ws: Information Literacy process the renaming of the verbs to a “w” word seems counter productive and could suit junior secondary students. The roles suggested for students, teachers and technology make this a similarity between the N.S.W. model and something to consider in the ILA. Overall these models list valuable verbs and processes that will be utilised in the information search process.

References:

Kuhlthau, Carol. (2010). Guided inquiry : school libraries in the 21st century School Libraries Worldwide, 16 (1), 1-12.

Kuhlthau, Carol C. ; Maniotes, Leslie K. & Caspari, Ann K. (2007). Chapter 2: The Theory and Research Basis for Guided Inquiry in Kuhlthau, Carol C. ; Maniotes, Leslie K. & Caspari, Ann K, Guided inquiry : learning in the 21st century, Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited.

Kuhlthau, C.; Maniotes, L. and Caspari, A, (2012). Chapter 1 : Guided Inquiry Design: The Process, the Learning, and the Team. In Kuhlthau, C.; Maniotes, L. and Caspari, A, Guided inquiry design : a framework for inquiry in your school, (pp.1 – 15). Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

An Essay – a synthesis of the annotated bibliography – the light has been turned on!

The investigation of inquiry based learning was a journey of questioning and has led me use and improve my information searching processes. This search process has demonstrated the complex nature of learning. The nature of inquiry is to question, find answers and then reflect upon that new learning. In this synthesis we see inquiry learning as pedagogy where “any conscious activity by one person designed to enhance learning” (Watkins & Mortimore, 1999, p. 3) will powerfully transform the way deep lifelong learning occurs. Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari recognise learning as a “holistic experience” (2007, p. 27) where there is an opportunity for teachers to differentiate and use multiple intelligences in the process. The sources referred to in the annotated bibliography support the view that an information investigation is a process. This method involves questioning, information searching and the ability to reflect upon the process. It is a complex method that requires targeted point of intervention support. There are a variety of inquiry models to consider but all seem to have three things in common; questioning, searching and are cyclic in nature.

Guided inquiry models that I have investigated all hold questioning “at the centre of the learning experience” (Harada & Yoshin, 2004, p. 2). The recognition of effective, strong questioning was articulated by Rusche & Jason and reference made to the utilisation of questions “as a sounding board to express an original idea or undeveloped analysis” (2011, p. 340). Brunner’s Inquiry Process begins in the same way where students pose real questions. Importantly “student questions are the building block of engagement” (Rusche & Jason, 2011, p. 340) and provide educators with insight into student learning. Purnell and Harrison (2011) recognise that inquiry begins with questioning but that it is reliant upon the effective use of the process in order to develop student knowledge and skills. Green (2012) reinforces this and refers to the use of personal and authentic questions and the importance of collaborative inquiry where the teacher and student work freely.

The Information Search Process (ISP) is interwoven by nature and requires “guidance, instruction, modelling and coaching” (Kuhlthau & Maniotes, 2010, p. 18). This is supported by Green (2012) who identifies that inquiry also needs to be collaborative and guided in order to be successful. Sheermann (2011) maintains this and presents findings that demonstrate the learning gains from a collaborative project where the teacher and librarian shared similar goals. FitzGerald (2011) and Shannon (2002) refer to the Kuhlthau Model of the ISP. FitzGerald (2011) provided detailed descriptions of how students were feeling during the process and makes reference to prior knowledge for formative assessment. Shannon (2002) shared about the inclusion of a constructivist approach where feelings influence the development of learning and that there are stages, intervention zones and mediation levels. The idea that inquiry learning is a cycle is strongly conveyed in these studies.

The readings refer to the inquiry process as a learning cycle and share common ideas of inquiry strategies and the need for teacher support. Green importantly recognises that “inquiry learning is a core responsibility for all teacher librarians. It is often the most challenging part of the role, requiring many skills including intuition, insight, collaboration, flexibility and, at times, enormous amounts of persistence” (2012, p. 19). The recognition of the Middle Years Program model of inquiry adds credence to this due to its “fluid, differentiated and non-hierarchical structure” (Green, 2012, p. 20) where students are able to freely move between awareness and understanding and move to reflection and then action. This is supported by Colburn (2000) who also sees learning as cyclic. Pernell and Harrison (2011) share the same cyclic idea but take this one step further by having a backward design process.

Guided Inquiry learning enables teachers to work collaboratively. There has never been a more important time in education where the complex process of questioning and searching can be targeted successfully through scaffolding and guidance. With a Guided Inquiry model quality learning experiences are achievable because of the targeted point of intervention, giving support for all involved. Students have ownership to produce new learning through authentic situations and teachers gain confidence to be innovators of change. FitzGerald states that “the Information Search Process lies at the heart of Guided Inquiry” (2011, p. 1). This process is essential for developing independent lifelong learners, people who are ready and able to use their creative skills when solving problems and issues. Where everyone involved can make the most of every opportunity presented to them in their life, becoming learners who have the potential to develop innovative new ideas in the future.

References:

Colburn, A. (2000). “An inquiry primer”. Science scope (Washington, D.C.) , 23 (6), p. 42.

FitzGerald, L. (2011). The twin purposes of Guided Inquiry: guiding student inquiry and evidence based practice. Retrieved from: http://www.curriculumsupport.education.nsw.gov.au/schoollibraries/assets/pdf/guidedenquiry.pdf

Green, G. (2012). Inquiry and learning : what can IB show us about inquiry? [online]. Access; v.26 n.2 p.19-21; June 2012.

Harada, Violet and Yoshina, Joan. (2004). Chapter 1 : Identifying the inquiry-based school in Harada, Violet and Yoshina, Joan, Inquiry learning through librarian-teacher partnerships, Worthington, Ohio: Linworth Publishing, pp.1-10.

Kuhlthau, Carol C. ; Maniotes, Leslie K. & Caspari, Ann K. (2007). Chapter 2: The Theory and Research Basis for Guided Inquiry in Kuhlthau, Carol C. ; Maniotes, Leslie K. & Caspari, Ann K, Guided inquiry : learning in the 21st century, Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited, pp.13-28.

Purnell, Ken and Harrison, Allan.(2011). Inquiry in geography and science : can it work? [online]. Geographical Education; v.24 p.34-40; 2011.

Rusche, S. N., & Jason, K. (2011). “You have to absorb yourself in it”: Using inquiry and reflection to promote student learning and self-knowledge. Teaching Sociology, 39(4), 338-353.

Sheerman, Alinda. (2011). Accepting the challenge : evidence based practice at Broughton Anglican College. [online]. Scan; v.30 n.2 p.24-33; May 2011. Watkins, C., & Mortimore, P. (1999). Pedagogy: What do we know? In P. Mortimore (Ed.), Understanding pedagogy and its impact on learning. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Shannon, D. (2002). Kuhlthau’s information search process. School Library Media Activites Monthly, 19(2), 19-23.